Shalach Manot

"Women of the Amorgos island, 1911."

“Shirts! Shirts!”

The boy was standing in front of the mosque just down the street from his family’s house. Would you call it a street? It was dirt, it was never paved or stone, but as the men came out of the mosque, the boy sang out in a clear voice, “Buy a Shirt!”

He had said to his mother, “Zip, zip, you make them so fast, why not make them to sell? One seam here, one seam there, I’ll sell them for you. I’ll go in front of the mosque, and when the men come out I’ll make some money, and bring it home to you.”

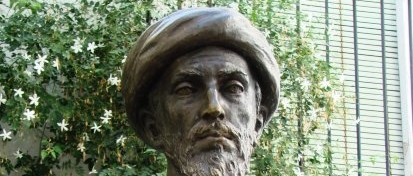

It was the Ottoman Empire in 1911, in a port across from Europe—on the Asian side of the Strait of Dardanelles. They were living in a magnificent nowhere-land, with melons in the attic, beehives for honey on the windowsill, his grandfather’s vineyards full of grapes, but with nothing much a man could do. Study the Torah—the Hebrew Bible—it was the most important thing. The men studied with the boy’s father on Shabbat. But it was not enough. His father had the shop, with kerosene lamps and the dishes and glasses that came in huge wooden crates from Austria, but how many dishes could you sell in Canakkale? His father sat in the shop and read the newspaper. He knew how to read, so he relayed the news to everyone. What was the news? What did it have to do with them? Slowly, week by week the newspapers came from Istanbul and raised the same questions day after day. The lid was coming off, you could watch it jitter and settle and jitter again, or you could think about it.

The boy’s mother was up at five every morning, sitting at the sewing machine. She sang as she worked, a steady breathing of thought and cloth strategy, her right hand on the wheel. She was like his father standing to pray, but she was seated with a firm hold on the earth, her foot on the treadle. Praying was breathing between here and God, and sewing was breathing between cloth and God, with a voice in Spanish words. The boy sat by her side, the cloth moved into creation while she sang. “Ken me va kerer a mi, ken me va kerer a mi? Who is going to love me? Knowing that I love you, my love for you is the death of me.” But if cloth could become shirts, sung and sewn into creation, that you could wear on your back, then nowhere could become somewhere and a man could grow up through life like the turning of the events in the Joseph story, until the powerful man wept to see his brothers, and they all wept finally and knew even a boy thrown into a pit could grow up to be a vizier.

A boy could grow to be a man, might grow tall.

First the men took off their shoes, lining them up in pairs. Then with their clay libriks they poured water on their faces and their uplifted forearms, the sky overhead bright as a blue pillow of light, the breezes cool. Inside they prayed on the tiled floors. They did want the shirts, the men as they came out of the mosque. How could you say no, they were cheap. Everyone needed a shirt at this price. Anyone would buy them, and it was the boy’s idea. He had been proven right. Once as a boy you’ve been proven right, thinking for the family, you can keep going, jumping up in the favor of your mother’s eyes, and your own eyes.

***

He was the oldest now. His oldest brother had been sent off to Jaffa to study the new science—agriculture. It was a scholarship from the Alliance Israelite Universelle. The very name of the school was like the bright wild shake of a tambourine to the mother and father, and to the five hundred Jewish families of the town. The boy himself went to the Alliance school in Canakkale. It was different from the ancient Talmud Torah with the children huddled around tables, taught by poor old shrunken men in raggedy beards. At the Alliance, Monsieur Toledano, the director who had studied in Paris, stood up tall and wore a top hat. The boy’s mother had insisted the next brother go along with the eldest to Jaffa, although it tore her heart out to let the two of them go. But the Alliance was right that they had to save themselves from being ground into the earth and had to find the sea of emancipation. The sea was big, the world was wide, although the town was tiny, clustered, and safe like a breeze-blessed paradise at the center of the world. The town was at the Narrows of the Dardanelles, the same straits that were a birth canal for Europe, with the snow cold waters rushing down from the Black Sea through the Bosphorus through the Sea of Marmara to here where the ships of the world went by. His mother’s rich brothers sometimes sat at the tables by the water (she didn’t have the money or, with six children, the time to sit there), drinking tea, watching the ships of the world pass by with their colorful flags. You could see Europe right across the Straits, it was right there.

***

The boy knew the smell of kashkaval because when he worked at the grocery that year, the owner asked him to carry a whole half wheel of it across town. It was heavy for him, so to brace himself he carried it high on his chest, but his nose could not move away and the cheese was so pungent it stank. That smell he knew well (and eventually he would eat kashkaval years later). What the boy never knew was about Ovid’s Leander, thousands of years before, swimming across the same straits in the terrible rushing current every night from Abydos on the Asian shore a short walk from Canakkale, to his goddess Hero across the water holding a light up in her tower. And he never knew about a limping rich English poet jokingly trying the same swim in the dark of night about a hundred years before the boy set up his gymnasium of branches and rope in a little garden. The boy did not know either about the nearby city of Troy, a half day’s walk away, being attacked by the Achaeans across this same water—the Dardanelles, the Hellespont—and all the tales sung and then written down about those wars, jealousies, wrenching deaths and armor. What the boy knew was that among the Jews of Canakkale, the men sang the Hebrew prayers every day, praising the same Ashem the Jews had sung to after Ur, in Egypt, in the desert, in Jerusalem, on the Iberian Peninsula, and here where they were welcomed to settle and sent ships for, in the Ottoman Empire.

* Shalach Manot is the pen name of a writer who lives in a New York City apartment looking out on a brick wall. Manot’s credits include fellowships from the Mellon Foundation and City University of New York; short stories, essays, and an NPR play about the Spanish Jews; and the new book, His Hundred Years, A Tale (2016), from which "Canakkale, 1911" was taken.