Netanel Miles-Yépez

La Conquistadora in Colcha Dress. Photo by Amitai Malone, 2013

Teresa May Duran is a respected Colorado santera who, like many latter-day practitioners of the art, took up ‘saint-making’ only later in life while raising a family and pursuing another career. However, in her case, the seeds of what would become an obsession with this New Mexican and Coloradan art form seem to have been planted early.

Born in Pueblo, Colorado in 1955, her father, Henry Martinez King, was a barber and part-time rancher, while her mother, Eva Barela Maldonado, raised Teresa and her siblings at home. Both parents were from Huerfano County in Southern Colorado, her father being born and raised in Red Wing, and her mother in La Veta, in the foothills of the Spanish Peaks.

Teresa’s great-great grandfather, José Victorio Maldonado, who was born in Taos, homesteaded a thousand acres at the base of the Spanish Peaks in the 1870s, where he raised sheep and grazed cattle. This was considered a family tradition, as the Maldonados were originally shepherds from the Basque region of Spain.

Teresa’s mother, Eva, came from a large family of 14 children, and only attended school up to the third grade, as she was needed at home to help her mother with chores and to take care of the younger children. Among her chief duties were making the tortillas and bread for the family. Indeed, she was so identified with this task that her brothers and sisters called her the panadera, the ‘bread-maker.’ According to Duran, “She was the most wonderful cook, and very creative. She was a great inspiration in my life.”

Teresa’s paternal great-grandfather was James King, an Anglo homesteader who came up the Santa Fe Trail around 1870. His son, Charlie King, later married into a Hispanic ranching family in Huerfano County named Martinez, originally from the Taos area.

In 1965, when Teresa was about ten years old, her father Henry bought a small ranch in Chama, Colorado, to which the family would retreat on weekends. Shortly after he had purchased the land, he took Teresa with him as he went to look over the property. About 300 feet from the house was an old, two-room adobe structure with a cross out front and a padlock on the door. Breaking the padlock, her father entered the dark structure with Teresa trailing just behind. It was a morada, a meeting-house of the Penitente Brotherhood, a Hispanic fraternity of Catholic laymen who functioned as pious guardians for the communities of Southern Colorado and New Mexico.

Entering the starkly contrasting light and shadow of the morada, Teresa describes her experience that day and what she saw next:

"We walk in and we see the first room, which was like a storage room, where they kept the things they used in their ceremonies. That’s where all the noise-makers [matracas] and the flagellation whips [disciplinas] were kept. I remember they had a wooden candle-holder with candles all in a pyramid-like form. Both the wooden noise-makers and the candle-holder were huge!

"Then we walk into the chapel. The altar was still intact, and there were bultos at each side of the altar. I remember there were also chests filled with clothes that they used to change out the clothing of the statues for different ceremonies. And there were retablos along all the walls, along with Stations of the Cross.

"Now, my dad was a very tall man, about six foot, and he wore cowboy boots and a hat all the time. And here I was this little girl, you know, ten years old. Well, we walked into that room, on those old warped wood floors, and his cowboy boots and his being a big man caused the floor to shake; and all of a sudden, the hands on the saints started to move! ‘Cause, you know, the old bultos were not fully wood. The body of it is like a cloth doll, and they attached the carved hands and head to that so they could dress it like a doll. So when my dad’s weight shook the floors, the hands started to sway, and my father, right away, starts making the sign of the cross, and I’m looking around with my eyes wide, like, 'What’s going on in here!'”

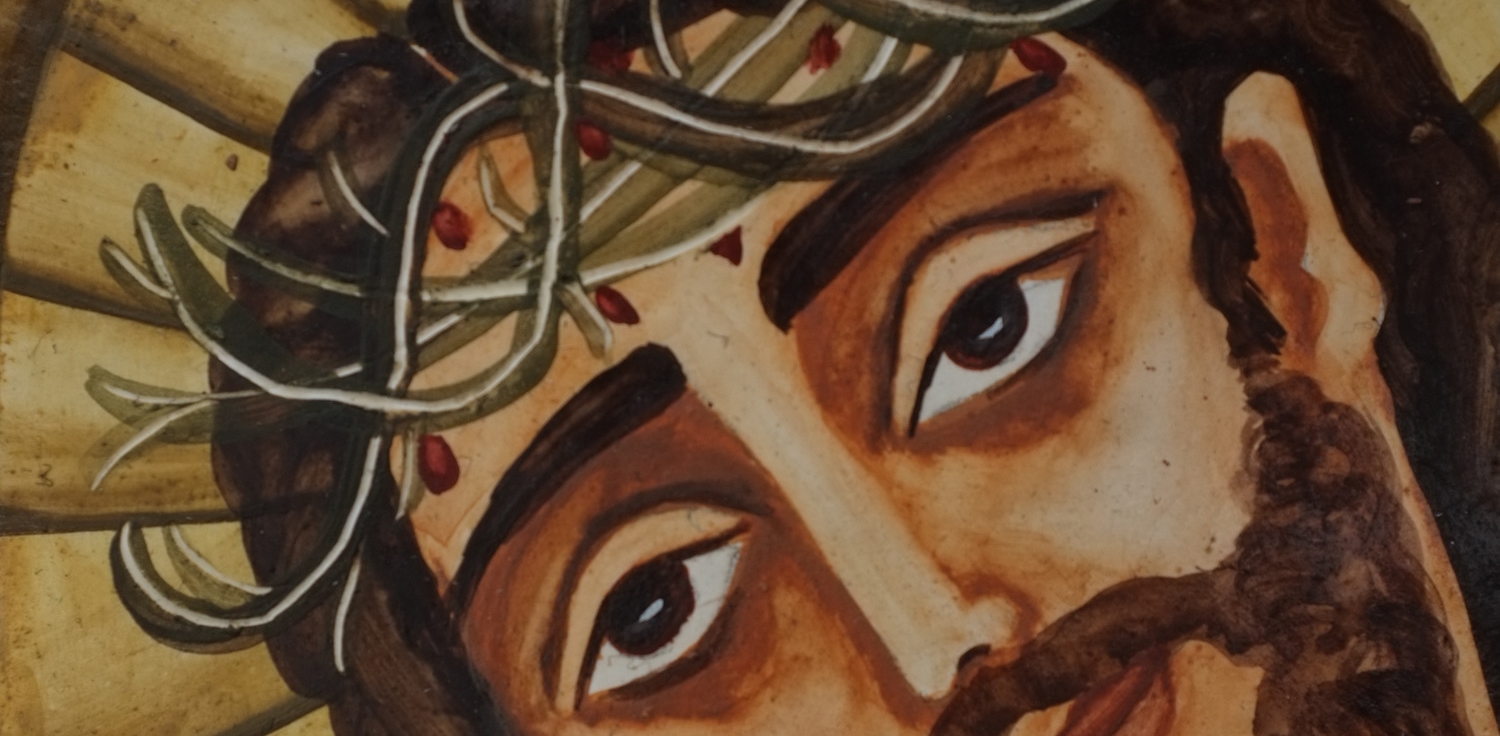

Christ Crucified. Photo by Amitai Malone, 2013

After this experience, Teresa’s father would tease her, “Don’t go by the morada at night!” But it was too late; she was magnetically drawn to the building and its objects. For the next three or four years, she would go and explore the morada on her own, looking at its retablos and bultos, picking up the big matracas and swinging them until they made their distinctive sound. But, after a time, her father began to worry over the burden of being the guardian of these sacred objects, no longer in use and soon to be extremely valuable. So, around 1969, he sought out one of the last penitentes left in the area, a man in his 80s named Vigil, and asked him if he would come and remove the belongings of the Penitente Brotherhood.

About six months after the artifacts had been removed, Teresa remembers how a little twister came down from the mountains and hit the morada, destroying the roof and throwing all the vigas (beams) off the top of the adobe structure. The twister landed right on the morada, and strangely enough, touched nothing else in the area. Teresa commented on how a neighbor, Abe Bravo, had a large pile of loose hay just fifty yards away from the structure that was completely undisturbed. Without the roof and the vigas, the old adobe building was quickly worn down by the elements until only the foundation remained.

As a child growing up in Pueblo, Teresa described herself as a mediocre and indifferent student who, nevertheless, always loved to draw and make things. “I used to get into trouble by drawing on things,” she remembers. “One time, I made all these little puppets out of my dad’s black electrical tape—He was really angry! Another time, while my mother was sewing, I took a pair of her scissors and pulled up the fabric of my dress into little peaks and cut the tops off to make patterns. By the time my mother looked at me, I had holes all over my dress! So I think I was fascinated with shapes and colors since I was really young.”

After graduating from Pueblo’s South High School in 1973, Teresa went to live with an aunt in Santa Ana, California for a year, where she worked in a factory, soldering diodes on computer boards. Unsatisfied with this work, she returned to Colorado to go to college. In high school, she had been in a program called Upward Bound, which targeted students from low-income and minority families for special attention in order to prepare them for college. With the confidence she had gained in this program, she applied and was accepted to the University of Southern Colorado in Pueblo, where she studied social work. But, even then, she could not wholly abandon her love of art and enthusiastically took a class on the art of the Southwest. As a part of the class, the students took a special field trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to see the traditional retablos and bultos in the museums there.

When she had completed her Associate Degree in human service work, Teresa was undecided about her next steps. She began to take classes toward a Bachelor’s Degree, but wasn’t completely certain of her aim. So she went to live with her sister in Santa Fe for a time to consider her options. Not long after, while visiting her parents in Pueblo at the Christmas holiday, she ran into a young man she had once dated. His name was Ernest Duran Jr. and he was studying law at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Happy to have reunited, but doubtful about long-distance relationships, he asked her if she would come to Boulder. To his surprise, she said, “Yes,” and the two were married shortly after.

After finishing Law School, Ernest got an internship with the National Labor Relations Board in Houston, Texas, where the couple lived for a short time. He was then offered a job with the same in Denver, where he afterward had a long career in labor relations and the couple raised their three children—Ernest III, Crisanta and Caroll.

When her youngest child was about three years old, Teresa decided to finish he Bachelor’s Degree at Metropolitan State College of Denver. The stress of social work no longer seemed manageable while raising her children, so she pursued a new degree in business administration. She later got a job working for the City of Arvada in affordable housing, and after two years, went to work for the State of Colorado, developing affordable housing all over Colorado. Eventually, she worked her way up to Deputy Director. While filling-in as Interim Director over a six-month period in 2009, she was offered the position of Director. But, at that point, Teresa decided, “Time is short,” and retired so that she could dedicate herself to painting santos full-time.

Over the years, she had painted whenever she could find the time, mostly as a hobby. But sometime in the early 1990’s, Teresa bumped into an old friend from the University of Southern Colorado—Meggan Rodríguez DeAnza—while attending a Chicano art show at the Denver Art Museum. Although they had lost touch many years before, they recognized one another immediately. In the interim, Meggan had gotten her Master’s Degree in Art and had pursued a career as an art teacher in the Denver school system. As both shared a love of painting, the two began rekindle their friendship. At the time, Teresa was mostly painting watercolors and showed them to Meggan, who suggested that she might be good at painting retablos. She then showed her some that she had painted herself while living in Taos, New Mexico, and Teresa fell in love with them.

Teresa Duran holding a retablo. Photo by Amitai Malone, 2013

Encouraged and inspired by Meggan’s work, Teresa slowly started to imitate and produce her own renderings of traditional santos in acrylic paint on pre-cut wood from the store. Then, in the early 1990s, she participated in an art show at the Denver Botanical Gardens for the Chile Harvest Festival. There she met a retablo painter and college professor named Juan Martinez who told her that she could easily work with the traditional materials, using the traditional techniques. He said, “Teresa, this is what you do” and began to tell her how to make the gesso, giving her ‘round about’ measurements. Teresa remembers, “I wrote it down—and being the daughter of a fabulous cook that could throw everything together—he told me things, and I picked it up very quickly. I mean I just went to the stove and I did the animal skin glue like he told me, put the gesso together, and it just came out!” But she did not make the transition to natural pigments as quickly. She first began to paint in watercolor on the homemade gesso, and then tried a combination of watercolor and natural pigments before becoming comfortable enough to use the latter exclusively.

Once she found that she could actually do it all herself, Teresa became passionate about the traditions and the entire process of saint-making. She began to buy the available books on santos and the work of santeros, and to ask questions of whomever was willing to teach her a thing or two. In this way, she learned where should could obtain cochineal, how to cook-down chamisa, and how to use alum to make her colors more vibrant. She also started to study Christian symbolism and sacred art in her spare time, especially Byzantine and Spanish Colonial art (the influence of which are both still visible in her work). On vacations in the American Southwest and South America, she and her husband made a point of visiting places that had examples of Spanish Colonial art as it developed in these regions; and in each of them, Teresa found new inspiration which she brought into her painting. Indeed, her passion for her new craft and the use of natural materials even started to creep into her professional life. Working for the state, Teresa often had to travel around Colorado inspecting housing and meeting with other public officials. And often, in the course of a car ride through the mountains, colleagues would not be surprised to hear her cry out suddenly, “Stop the car! Look at that dirt! We gotta’ pick up some of that dirt!” Then they would watch in amusement as she got out of the car to collect a little red or black dirt in a cup or bag to take home and use as a pigment.

Through the years, Teresa’s painting has become more refined as she has achieved greater mastery over the medium. Nevertheless, her distinct style and bold presentation of evocative imagery has remained a constant from the beginning. Her work is distinguished from that of many others by her attention to symbolic detail and cultural context, by the incorporation of stylistic elements from both Spanish Colonial art of different regions and Byzantine iconography, and by her excellent color work. In each piece, there is a strong sense of story and the artist’s commitment to depicting an important spiritual or moral ideal.

Although she received early recognition as a santera—her work being used on the posters for the Denver Chile Harvest Festival in 1995 and the “Santos: Sacred Art of Colorado” exhibit at the O’Sullivan Arts Center of Regis University in 1997—Teresa found it difficult to find enough time for her passion until she finally retired in 2009. By then, she had already been a santera for 18 years and had participated in many shows and festivals in Colorado and New Mexico. Nevertheless, she had never applied to the famous Spanish Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was something she felt she simply could not manage while working for the state. But as soon as she retired, she set to work on the difficult application process for the 2010 Market, and to her great surprise, was accepted on her first attempt. Since that time, Teresa has participated in both the Summer and Winter Spanish Markets every year, and continues to participate in exhibits and shows throughout Colorado and the greater Southwest, including the annual Rendezvous & Spanish Colonial Market of the Tesoro Cultural Center in Morrison, Colorado.

Today, Teresa and her husband divide their time between their home in Arvada, Colorado, and their ranch in Las Animas County, from which they can view the Spanish Peaks. When they are not traveling to a show, they like to visit different countries where Teresa can find new inspiration. Most recently, they visited Israel to soak up influences from the land of the Bible and the birthplace of Christianity.

Teresa May Duran. Photo by Amitai Malone, 2013