By Arthur Green and Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

Rabbi Arthur Green is one of the preeminent authorities on Jewish spirituality, mysticism, and Hasidism today. A student of Abraham Joshua Heschel, Green has taught Jewish mysticism, Hasidism, and theology to several generations of students at the University of Pennsylvania, the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, Brandeis University, and Hebrew College, where he is currently Rector of the Rabbinical School. Some of his recent books include: Ehyeh: A Kabbalah for Tomorrow and Radical Judaism. He lives in Newton, Massachusetts.

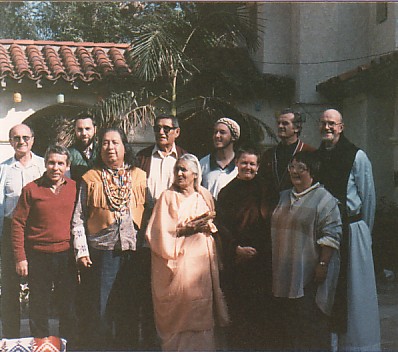

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, better known as Reb Zalman, was one of the world’s foremost teachers of Jewish mysticism and Hasidism, as well as the father of the Jewish Renewal and Spiritual Eldering movements, and one of the pioneers of ecumenical dialogue. A student of the 6th and 7th Lubavitcher Rebbes, Schachter-Shalomi went on to teach Hasidism and Kabbalah, as well as Psychology of Religion, at the University of Manitoba, Temple University, and Naropa University. Some of his last books include: Geologist of the Soul and Foundations of the Fourth Turning of Hasidism. Reb Zalman passed on in July of 2014.

In this dialogue, the root metaphors of ecumenical discourse are discussed by two modern masters of the Jewish tradition like a page of Talmud, l’shem shamayim, 'for the sake of heaven.' The dialogue was excerpted from a longer conversation that took place in Reb Zalman’s home in Boulder, Colorado on August 19th, 2001. It was originally transcribed by Ivan and Temima Ickovits and later edited for inclusion in an early issue of Spectrum: A Journal of Renewal Spirituality (Volume 3, Number 2, Summer-Fall, 2007).

— N.M-Y., editor

ZALMAN SCHACHTER-SHALOMI: Is the earth alive? Once, it was considered idolatry to ascribe consciousness to the earth and the stars. Now we talk about 'vibrations' and 'energy,' and it is more acceptable to say that they are consciousness. We can even speak of a galactic consciousness, or a solar consciousness.

This is why I feel a connection to the traditional Melekh Ha’Olam, the 'World Sovereign' description of God, because this is a Gaian God with whom I can have a connection. With a Solar God, in a manner of speaking, the distance is too great; it takes the Sun approximately 250 million years to make one circuit around the galaxy, and my experience has little to do with that galactic time-scale. But when I say, Melekh Ha’Olam, speaking with the Gaian-consciousness of the Global Brain, I can say that every religion is like a vital organ of the planet, and we need to have all the religions. This moves us away from the triumphalist[1] point of view to one that is organismic.

Then comes the question, “How does the Universal Mind want to be addressed?” It needs personas (partzufim), metaphors, and forms through which we can get to the uniqueness of the Universal Mind, and these are what we find in the different religious traditions. If it appears as a woman, looking like Mary, the mother of Jesus, we might not feel that this is appropriate for us as Jews. But how should the Divine Presence (Shekhinah) appear to the imagination? We need to have it in a form that the heart can recognize. This is what I make of the sentence, dibrah Torah bil’shon b’nei adam, it comes as it has to come to each individual awareness.

When other Jews criticize my acceptance of non-Jewish spiritual traditions, I ask them, “Do you believe in God’s special Providence (hashgahah pratit)?” And if they do, then I ask, “Do you think God was asleep when Jesus was born? Or when the Buddha was born?” If God’s Providence is true and we believe in 'general souls' (neshamot klaliyot), then how else can we see such souls as Jesus and the Buddha, except as general souls through which the Divine-flow (shefa’) comes through to people?

ARTHUR GREEN: We are very close on this issue, though I think I want the religions to be seen as 'garments' (levushim) rather than 'organs,' because I want to say that “the One is one and whole in itself.” It is seen in different vessels as It addresses Itself to different civilizations. Garments clothe the body, but organs are part of the body, dividing God, as it were.

I think every mountain, every tree, and every flower is a garment (levush) for the One. We believe in biological diversity, in cultural diversity, and spiritual diversity, because the planet needs to recover the spiritual truth that has been lost in the modern world. And for this healing, we need to preserve all the diversity we can; but I think I am still more comfortable with the language of garments than the organism.

SCHACHTER-SHALOMI: I understand your point, but the problem with garments as opposed to organs arises around the question of the collaboration organs have with each other; there is inter-dependence with organs.

When I have dealt with health problems in the past, I really began to understand that the kidneys and lungs share a connection—that the kidneys and the heart share a connection, and that each one influences the other to find a balance for the whole. There is a book by Sherwin Nuland, called How We Die, in which he says, it is a mistake to say that someone died from a 'heart attack,' because the rest of the organs had to give consent to that as well. That is to say, they were all getting fatigued in the process.

It used to be that people would say, 'she' or 'he died of old age.' But now, because the medical profession wants to find the 'culprit,' we no longer acknowledge that the organism as a whole begins to shut down. Nuland writes that the mutual influence of the inner organs is important. So when I look at the organismic understanding of things, it is better to me than the flatland democracy, with no distinctions and hierarchy. Some people say, 'everything is the same,' but it isn’t. With the organism, we have distinction and inter-dependence.

GREEN: I understand that “your intent is desirable,” as it says in the Kuzari, but what of the question of the supernatural origins of the traditions? I want to say something that goes like this:

There is the One Universal Being, a line of life present in all things, undergoing the whole evolutionary process, struggling to manifest itself, seeking to be known. It is a Creature seeking a garment for Itself, one which can ultimately have self-awareness, that can ultimately stretch its mind to be aware of this greater Whole. This One Brain manifesting all of our brains, manifesting all of our cultures, needs of us, calls upon us, to know It, to recognize It. And we, as people and cultures, then create all the forms. We create all the forms through which It is known, whether those forms are the Eucharist, the shalosh regalim, the chakras, the language of metaphysicians, or the language of Buddhist angelology; whatever these forms are, we create them. We create them in response to an inner call from the One, which says, “Know Me!”

If you say, “organs,” you are making them more part of the One, rather than the human response to that inner call, and this is why I still prefer 'garments' to 'organs.' I do like the inter-dependence of the organic relationship, but you seem to be saying they are essential revelations, rather than human responses.

SCHACHTER-SHALOMI: No, this isn’t the way of it for me. The first cells are called stem-cells. Stem-cells are generic cells that can become particular cells when the body needs them to do a unique task. Now, when I look at the Earth, I see that species are interacting in this same way. What is it that salmon spawn eat? What is it that comes from the old fish that has died? Everything has to become everything else! I see this as an organic issue, and this is the reason that I feel strongly about the specificity of organs.

If I say it is a garment among other garments, it loses some value. But if you say it is a 'vital organ,' then they are not something one can divest easily. This is why I want to counter triumphalism by saying, if the heart were to say, ‘the whole body can exist by the heart alone,’ without the kidneys, without the lungs, then it is obvious, isn’t it, that the body is going to die! That is why I want to make the total inter-dependence more palpable.

GREEN: Which tradition do you want to make 'the heart,' and which one 'the kidneys'?

SCHACHTER-SHALOMI: Each tradition always wants to claim the heart.

GREEN: Yehuda Halevi’s Kuzari makes someone else the kidneys; it’s not much of a concession.

SCHACHTER-SHALOMI: Yes, and when I was reading Emanuel Swedenborg,[2] I found that he has a Maximus Homo, a primordial human corresponding to Adam Kadmon. But, unfortunately, the Jews are the rump, the back-side. People will designate as they will.

GREEN: Are you sure that these are all vital? Let’s choose a tradition other than our own. Let’s suppose that Zoroastrianism and the Parsis disappear; too many of them become middle class, they move West, intermarry, and their tradition disappears. Is the body of the Universe, the mind of God, going to get sick because of that? I don’t think so. It will survive. Certainly, It would be diminished because of that. We are poorer for not having Dodo birds, and I regret that the Universe doesn’t have them, but the Universe has made itself new garments and has gone on; they have planted what they needed to plant into the civilizations of the world, and I don’t think there is a vital organ missing.

SCHACHTER-SHALOMI: The psychologist Alfred Adler wrote about how the body compensates. If you have only one kidney, you can still do quite a lot. Even without a gall bladder, you can still survive. That is true. But, I still feel that there is a contribution that gets lost. I want to say, 'As a Jew, I need to be a Jew, because I am making a contribution, not only for myself, but also for the planet.' The better a Jew I am, the better the contribution I make. The better a Catholic Christian is, the better contribution she or he makes. But then, I don’t speak about garments that you can take off or put on. That is why I like organs.

GREEN: The difference is essential.

Notes

1. Triumphalism is the belief that one’s own spiritual tradition will 'triumph' in the end, all other traditions being proven false.

2. A Christian mystic and scientist known for his great works, Heaven and Hell and the Arcana Coelestia.